Wilderness is often imagined as an untouched, dramatic landscape— a place to escape the human.

That’s how wilderness is depicted in an 1896 photojournal that currently resides in the Princeton University archives. The author of the journal, John Henry Purdy, was a New York socialite, invited by his friend, the railroad magnate William Seward Webb, on a 30-day hunting trip to Yellowstone National Park.

Purdy was thrilled by the chance to go West. He seems to see Yellowstone as a place to leave behind the fetters of polite society and embrace a rugged masculinity. Of the West, Purdy writes, “Here is no pride of birth nor vain tradition, but each hardy settler is entirely willing that his glorious past and high-sounding patronymic be forgotten.”

Yellowstone historian Chris Magoc explained that easterners’ romanticized notions of Western wilderness were partly shaped by anxieties about the future of masculinity and the nation’s character in the wake of Frederick Jackson Turner’s declaration that the frontier had closed.

“In the 1890s, it’s becoming urbanized,” Magoc said. “There’s canned food that’s coming just around the corner. The softening of men, the domesticating of men and manhood, the loss of one’s manhood, this is of grave concern.”

But reading the journal, it becomes clear that 1890s Yellowstone was not exactly an untouched wilderness. It had been commodified in significant ways for the white, upper-class tourist. The men traveled in private train cars to the park. They dined at hotels along the way. In the journal’s sprawling photos, taken by the park’s official photographer F.J. Haynes, the tourist presence is palpable.

Magoc said that the Northern Pacific Railroad, which had pushed for the park’s establishment and had monopolized the park’s hotels and restaurants, emphasized the human presence in their marketing.

“I’m thinking especially of the Wonderland guidebooks,” he said. “In those guidebooks, you see maybe a montage of the geyser basins, which were kind of menacing and alien, like a moonscape. And then right smack in the middle of the page, you’d have the Fountain Hotel or the Grand Canyon Hotel— insinuating the human presence and ensuring travelers that the place was being made into an accommodating tourist environment that was being domesticated.”

The notion of an untouched, separate wilderness is also undercut by park officials’ deliberate efforts to remove the Indigenous peoples who had lived in and visited Yellowstone’s land for thousands of years.

Magoc added that at the same time as regulations had banned Native Americans from the park, “you have the popular notion being promulgated in travel accounts and newspaper articles and so on, that Native Americans were superstitious of the park and that they just didn’t travel in the park.”

Despite regulations that prevented Indigenous people from accessing the park, tourists continued to rely on their services for guiding and hunting. In the case of Purdy and Webb’s party, two Lakota guides accompanied them, Baptiste Garnier and Grant Short Bull.

In one image in the journal, F.J. Haynes seems to want to depict a camaraderie between the men, with Black park soldiers, Native Americans, and white men standing and sitting side by side.

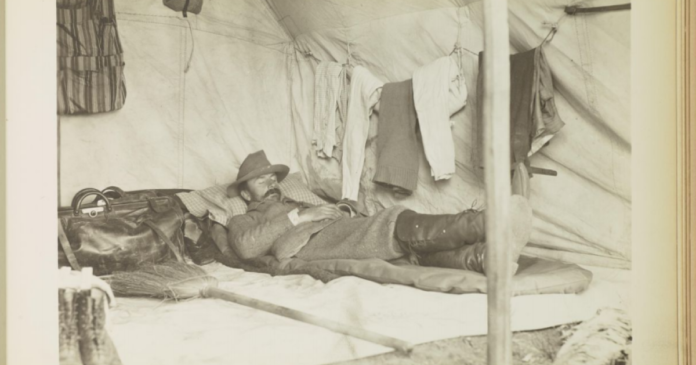

But the last photograph in the collection has a lot to say, too. A man—perhaps Purdy himself—lays down, sleeping in his tent on what looks like a comfortable pillow, his boots laced, and his leather luggage beside him. The wilderness is somewhere outside the confines of the cozy tent. Maybe Purdy arranged that photo last for a comedic purpose—to show an audience back home, perhaps, that the group wasn’t truly roughing it. That impression sticks with the viewer. In 1896, Yellowstone was not necessarily a place of untouched, rugged wilderness. Nor was it a space that all Americans could access equally. Instead, it was, for the upper-class white tourist, a place of leisure.