As international tourism lurches back to life, can we continue to support growth in one of our most polluting industries? And will doing so lead to fundamental changes in the management of our national parks? Perhaps we’ll find answers on the scenic Milford Road in distant Fiordland. Charlie Mitchell reports.

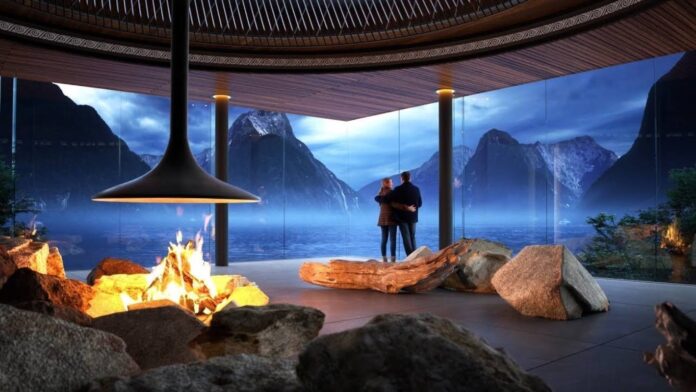

A couple relaxes in a cavernous room, gazing out at the fiord. A comforting fire crackles behind them.

Wooden buildings peek from lowland beech forests, and cyclists carve through golden grasslands. A cable car groans uphill, destined for a hanging valley that ends with a waterfall, pristine water crashing into the sounds.

This could be the future of Milford Sound Piopiotahi, according to a promotional video and an accompanying master plan.

READ MORE:

* Do we want tourists with ‘budgets of $20 a day’ back when the borders reopen?

* Taming the crowds: rethinking the tourism future of Milford Sound/Piopiotahi

* Southland visitor numbers expected to soar

* Milford Sound Tourism investigating options to parking congestion

It is elegant, environmentally conscious, and vaguely Scandinavian. Unsurprisingly, some images are taken from Pinterest, the internet mood board for those seeking aesthetic perfection.

Above all, Piopiotahi is quiet.

For years, authorities have grappled with the future of New Zealand’s heavyweight tourism destination.

Milford Sound – the mislabeled (it’s a fiord) and so-called “eighth wonder of the world”, well-known to Māori but largely overlooked by European settlers – has in recent decades become emblematic of both New Zealand’s scenic riches and its rollicking tourism industry.

MILFORD OPPORTUNITIES PROJECT

A concept image for the Milford Opportunity Project’s master plan for Milford Sound.

In 2013, Piopiotahi had 466,000 annual visitors; five years later, it had 883,000. Before the coronavirus pandemic, annual visitor numbers had been projected to reach 2 million by 2035.

Most of those visitors are funnelled into the summer months. Since 1991, the Fiordland national park’s management plan called for no more than 4000 people to visit Milford Sound each day, which was deemed to be the limit for environmental sustainability.

At the time, it was a high bar. But over the course of two months in 2018, it was breached on 20 separate occasions, and on February 22 – Chinese New Year – daily visitors reached the highest level yet at nearly 6000.

Despite a near doubling of visitors, there has been little improvement in the tiny village’s infrastructure or its resilience.

Milford Opportunities Project

A concept image shows the potential for a cycling path and accommodation.

The runway for fixed-wing aircraft has potholes, and floods during king tides; electricity comes from a small hydroelectric scheme vulnerable to cuts; the stream of vehicles regularly overwhelms the small number of car parks, leaving buses clogging the foreshore.

The alpine fault brushes the entrance of the fiord, leaving the area exposed to a catastrophic earthquake. Research on the impacts of past earthquakes – which include large, mostly inescapable tsunami waves crashing through the fiord – should only be perused with an appropriate source of emotional support nearby.

Ngāi Tahu, as tangata whenua, has limited input into the management of the fiord and the area’s rich Māori history is largely unrecognised.

But some argue there’s a less tangible problem: Milford Sound isn’t being appreciated.

The vast majority of visitors are international tourists, most of whom stay in Queenstown, four hours away. They hop on buses in the morning which squeeze through the Homer tunnel between 11am and 1pm, arriving at the fiord at the same time.

The tourists leave in the afternoon after a few hours on a boat, having spent much of the expedition observing the landscape from a rain-stained pane of glass.

In 2016, to address some of these issues, the Government granted $250,000 to the Milford Opportunities Project (MOP), a Southland regional development initiative exploring options to “manage growing tourist numbers in Milford, aiming to maintain a quality experience for visitors while also increasing revenue”, a press release at the time said.

Brook Sabin/Stuff

The Milford Road, cloaked in forest.

It came up with a vision statement for Piopiotahi: “New Zealand as it was, forever.” A governance group was tasked with creating a master plan for this vision, which included representatives from multiple Government agencies (including the Department of Conservation), Ngāi Tahu, and the tourism sector.

Then came the pandemic. Visitor numbers crashed from record highs in 2019 to near zero in March 2020.

Of all the visitor destinations in New Zealand, Milford Sound was hit the hardest by the pandemic, with an 86% drop in visitor numbers in 2021 compared to 2019. Almost overnight, Milford Sound had time-travelled backwards half a century, to an era pre-dating the normalisation of international air travel.

It provided breathing space.

“Tourism at Milford Sound Piopiotahi cannot return to its pre-Covid state,” Tourism Minister Stuart Nash said in 2021, when the master plan was announced.

The master plan went further than some expected.

It proposed a wholesale re-thinking of the tourist experience, saturated with the language of “destination management”.

Instead of a road to a fiord, the Milford Corridor would become a stage-managed experience – one with “curated story-telling” and “sympathetic infrastructure” for the discerning tourist.

Foreign visitors would no longer be allowed to drive to the fiord. They would need to board buses (running on electricity or hydrogen) at a hub in Te Anau, from where they would trundle along the road, basking in the views (“reveals”) and stopping for breaks (“short-stop experiences”) at a series of attractions along Milford Road. Those would include a range of accommodations, Great Walk quality tracks, and cycling paths, many newly built.

Their arrival at the fiord – heightened through landscape design and the careful placement of infrastructure within a rearranged village – would be laden with a “dramatic sense of arrival”.

Achieving this vision would require serious changes. Cruise ships would be banned from the inner fiord, in part so they can’t block the iconic view of Mitre Peak. The rickety old runway would be replaced with a spine of regenerating bush, with fixed-wing aircraft displaced for a larger heliport. The ageing hotel and staff accommodation would be moved and replaced, likely with an eco-hotel of some sort.

Overseas visitors would pay a fee, likely between $50 and $200 each. Resilient structures to withstand natural disasters would be installed, significantly increasing the likely survival rate. The Māori history of the area would be acknowledged and woven throughout the experience.

Combined, the estimated cost of the infrastructure alone would total around $300m, documents underpinning the MOP suggest.

“We were asked to come up with something innovative, something challenging, something that will change the way tourism interacts with environment and conservation,” Dr Keith Turner, chairman of the governance board, said at the time.

“I feel we have done that and now the hard work of implementation and decision-making on how to implement it begins.”

Brook Sabin/Stuff

The dramatic landscape of the fiord are a favoured destination for tourists.

Dolphins in Queenstown

Many years ago, Juergen Gnoth noticed something new in the tourism ads for Queenstown: Dolphins.

“I said, what’s happening here?” he recalls. “There are no dolphins in Lake Wakatipu.”

The dolphins, he realised, were in Milford Sound, which was being advertised as a Queenstown attraction.

This unusual dynamic – where tourism at Milford Sound is inextricably tied to Queenstown, despite being nearly 300km away by road, in a different region, on the other side of a mountain range – has been the main driver of visitor growth at Piopiotahi.

Gnoth, a Professor of Marketing at the University of Otago, is sceptical about the MOP and its proposed re-imagining of the tourist experience.

One of its goals is to build up Te Anau – the town closest to Piopiotahi – as a tourist destination in its own right, and the new base for visitors to the fiord.

The problem, Gnoth says, is that Queenstown tourists and Te Anau tourists are different. Queenstown’s tend to be time-poor; they spend a lot of money but don’t stay for long. Te Anau’s visitors tend to be more rugged – they’re travelling around the South Island, doing hikes and walks, staying for longer.

“They are basically different segments,” he says.

“How do you suggest getting the average Queenstown tourist to become interested in Te Anau? I don’t think that you will, unless you actually change, through marketing strategies, the segment itself so that it becomes more homogenous between those two destinations.”

The broader problem, he says, is that the master plan does not seem to tie into a national strategy that deals with the long-standing problem of concentration.

Tourists are directed to a handful of locations – chief among them Milford Sound – at particular times of the year. A local strategy to make Milford Sound more appealing, without that tying into a broader strategy, risks making the problem worse, he argues.

He also questions the animating basis for the MOP: That it is overcrowded and unsafe. His own research suggests that view is a myth. And even if it was true, the MOP does not propose reducing visitor numbers – in fact, it allows for them to grow, albeit while spreading them out throughout the day.

“I’ve asked about 2000 tourists who visited Milford Sound, and they do not think it is crowded, noisy, or unsafe – quite the opposite,” Gnoth says.

“If you now want to double the numbers of visitors, even if you spread them out a little bit more… Somewhere, there is a contradiction in that. Either it is crowded or it isn’t.”

MOP’s director, Chris Goddard, says the aim is to make the experience better for everyone by removing the crush of visitors during the day: ”[The master plan] aims to ensure the visitor experience is excellent for everyone while protecting the sound’s unique conservation values and enhancing its cultural stories,” he says.

“Through all our engagement, stakeholders agreed there needed to be changes in Milford Sound Piopiotahi, even if they did not agree with everything that was proposed in the master plan.”

While the plan remains just that – a plan – there has been little wider debate about specific elements of the proposal.

Many involve elements of give and take. Amongst the most significant is a proposed cable car, which would take visitors from the lake foreshore to the top of Bowen Falls, one of two permanent waterfalls in the fiord.

It would be a show-stopping attraction for tourists, but would come at an ecological cost. The master plan process included a conservation analysis, which was unequivocal on the wisdom of that idea – a cable car would require significant and unavoidable vegetation clearance, it said, and was “not appropriate from a conservation perspective” – but it nevertheless made the cut.

On the other hand, the master plan proposes reinvesting money from the visitor access levy into conservation.

As the conservation impact analysis notes: “DOC’s current funding allocation from central government means that in many areas of Fiordland pest control is absent, or if present is little more than an ambulance at the bottom of a cliff.”

With a regular stream of money from tourists, could that start to change? It’s the tension at the heart of tourism’s future: Can it become a tool for regeneration?

Brook Sabin/Stuff

The views near the beginning of the Milford Road.

But perhaps one of the most significant proposals is also the least discussed. It’s about governance – who, or what, should run the transformed Milford Sound?

Today, that task mostly falls to the Department of Conservation (DOC). The reason is simple; it’s in a national park, and DOC is legally responsible for the management of national parks.

That includes running a concession system, which grants permission to tourism operators to conduct business in the park, ranging from guided walks to helicopter trips, in exchange for a small levy. DOC also oversees the management plans for each national park, which set objectives for how each one is run.

It’s no easy task. Under the law, DOC’s top priority is that national parks “shall be preserved as far as possible in their natural state”. It must also “foster” recreation, and “allow for” tourism. All three can be at odds.

DOC has been reluctant to use its powers to limit visitor numbers, so it instead accommodates the swelling ranks of visitors – and their environmental footprint – while trying to preserve the natural state of national parks.

It must do so with a tighter-than-optimal budget and a host of other responsibilities, including the not-insignificant task of battling the biodiversity crisis.

DOC’s performance on these fronts has been questioned.

The Fiordland national park management plan – which covers Milford Sound – has not been updated since 2007, and its visitor cap is not enforced. Landscape-scale predator control is infrequent. The tourism industry has long been frustrated with DOC’s first-in, first-served concession regime, which is marked by lengthy delays and privileges those who have existing concessions.

For its part, DOC says that it’s working with outdated legislation and processes, which are in the process of being updated.

“DOC acknowledges that complicated and dated legislation means using and navigating management planning and concessions can be challenging,” says Steph Rowe, the Deputy Director-General of Biodiversity, Heritage and Visitors.

DOC hasn’t given up on reviewing the Fiordland management plan – it “prioritises these reviews against its resources and this one has been classed as a priority,” Rowe says – but it will take time.

Amid these challenges comes the MOP.

Although it started as a regional committee, it was granted a broad remit: Its terms of reference encouraged it to think beyond what is legally possible.

In that spirit, its master plan recommended that instead of DOC running Milford Sound, control would be vested to a separate entity that would own and manage the infrastructure while also delivering DOC’s functions under the national park and conservation acts.

That would include running the park and ride service, and possibly even hotels and other tourism infrastructure: A significantly more hands-on approach to tourism in national parks than currently allowed.

All of this would require changing the law.

If that happened, Milford Sound would essentially become a bubble within a bubble: a special zone, within a national park, run by a one-stop shop that would do tourism and urban planning in-house. As one MOP document said, it “would set a precedent across the wider conservation estate and support for this option may give rise to more substantive policy issues”.

DOC says there are “currently no plans” for such a law change. But whether the master plan can be achieved without it is up in the air.

Documents supporting the MOP suggest the master plan cannot be done within the status quo. Of the range of governance options looked at, only the creation of a new entity was deemed to meet all the requirements: The most likely alternative, an enhanced version of the status quo, would be “unlikely to embed change to the degree that would meet stakeholder expectations”, the document says.

That leaves something of a stand-off.

If the Government agrees to change the law to enable the master plan – effectively diluting DOC’s influence in national parks for an entity that would deliver a tourism-driven master plan, with ongoing control of the village – is likely to face concerted opposition in some quarters.

Jan Finlayson, an executive member of the Federated Mountain Clubs (FMC), says the proposed law change is buried beneath a “lolly scramble” of initiatives at Milford Sound, and would have stark consequences for national parks more broadly.

“The lollies aren’t worth a commercial assault on our national parks legislation,” she says.

“If it can happen to Milford, it can happen to Aoraki, the glaciers, Abel Tasman – anywhere.”

Dr Rob Mitchell, a long-time tramper and mountaineer who wrote his doctoral thesis on sustainable tourism at Milford Sound, says the master plan appears to be a ploy to enable more tourism growth under the guise of sustainability.

It is being done so, he says, without proper public scrutiny. Heavily involved in the project, he notes, is the Ministry for Business, Innovation, and Employment (MBIE), an agency that has no statutory role in managing national parks.

“You could argue the MOP is a legitimate regional initiative that needs to be explored, but it has developed far beyond that,” he says.

“You effectively have a local committee (MOP) making submissions to Cabinet, with DOC – which is the statutory manager of the national park – being relegated to a minority role in this process. It’s highly unusual.”

(DOC says it has been an active member of the MOP, and it supports the process for the plan’s creation and the upcoming work to test its feasibility.)

In Mitchell’s view, there is a simple, democratic solution: Better resource DOC to update and enforce the existing management plan, which is the product of the wider community’s desires.

“Someone needs to stop the merry-go-round and go back to basics,” he says.

“There’s an assumption that everyone’s going to win out of this, but there will definitely be losers. And it’s important for those people to be heard at this stage before things go haywire.”

(Goddard, from the MOP, says the master plan is at the feasibility stage, and there will be consultation with a wide range of groups including recreationists, which will include a dedicated advisory group. Goddard has had “initial meetings with a wide range of interested people, including representatives from recreation groups and tourism operators”, he said.)

Tourism Minister Stuart Nash says there is strong demand from overseas visitors wanting to come to New Zealand this summer.

Visitors incoming

Over the coming summer, Milford Sound will welcome back international visitors. More than 100 cruise ships are expected to dip into the fiord, many of them carrying thousands of people each.

Hundreds of thousands more will travel through the Homer tunnel in buses and private vehicles, most running on fossil fuels. Many will have flown to Queenstown from Auckland, and to Auckland from their home countries, a modern miracle enabled by burning climate-heating aviation fuel.

The carbon toll of international aviation is inescapable. That is especially true for visitors to Piopiotahi – a particularly isolated enclave within a remote country. For all the master plan’s ambition, it cannot physically move the fiord closer to the rest of the world.

Unlike some parts of New Zealand’s economy, there is currently little potential to decarbonise international tourism. There are no technical fixes on the immediate horizon for the pollution from long-haul aviation.

Regardless of what happens at Milford Sound in the future, experts agree that tourism is at a turning point.

Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE) Simon Upton has written extensively about the need to reckon with the environmental damage caused by mass tourism, particularly its carbon footprint.

Among his recommendations are a distance-based departure tax and making future tourism infrastructure funding subject to environmental criteria.

Brook Sabin/Stuff

Milford Sound is one of New Zealand’s tourism jewels.

It’s a debate that has been a long time coming. As tourism became an increasing contributor to New Zealand’s economy – driven in large part by subsidies from successive Governments – there was little reckoning with its environmental impact.

“Tourism and sustainability is an oxymoron,” Juergen Gnoth says.

“The fact that tourists travel by air is one of the greatest hitches in the idea of making tourism more sustainable, so the only way of really doing it is creating slower travel.

“We have had an experience of more and more tourists coming no matter what we did over the last 30 years. So this sustainability idea is very, very difficult to manage, because we have no ideas for it, nor do we have any appetite, really, for it.”

The Government has said it wants to re-imagine tourism. An independent taskforce has given its own view, which would put the environment at the heart of the industry’s future.

But for decades, mass tourism has been an unstoppable force, in search of an immovable object. Why would we expect that to change now?

“Over those decades, there was lots of talk about needing to be committed to more sustainable tourism,” says Professor James Higham, of the Department of Tourism at the University of Otago.

“But in reality, tourism was like a juggernaut – it was impossible to divert. The result of this exceptional acceleration of tourism has been more environmental impact and less economic benefit.”

Sustainable tourism, Higham says, is a misnomer – at least based on current technologies. Any future strategy will likely involve us travelling less distance, for longer periods of time – “a back to the future sort of model.”

“I think there’s a general consensus that we cannot – and should not – return to the old pre-Covid tourism,” he says.

“But saying it and doing it are two different things, aren’t they?”